Complex Rotations

Multiplying complex numbers visually

June 17, 2022

My goal for this post is to provide a more intuitive and satisfying way to understand and solve problems with complex numbers. If evaluating \(z\) in expressions such as

\(z=i^{n}, \space n \in \mathbb{Z};\quad\quad\) or \(z=re^{i\theta};\quad\quad\) or even \(z=\sqrt{i};\quad\quad\) or even better \(z=(\sqrt{2} + i\sqrt{2})^{4};\quad\quad\)

leave you wondering where to even start trying to evaluate - good! By the end of this I hope that you will have the tools you need to evaluate these, and be able to explain them to others.

Feel free to skip over any of the following sections you already feel comfortable with.

- So What Are Complex Numbers?

- Graphing Complex Numbers

- Multiplying by i

- Multiplying on the Complex Unit Circle

- Leaving the Complex Unit Circle

- Solving Complex Problems

- Extra Challenges

So What Are Complex Numbers?

Let’s start with the basics. What is a complex number?

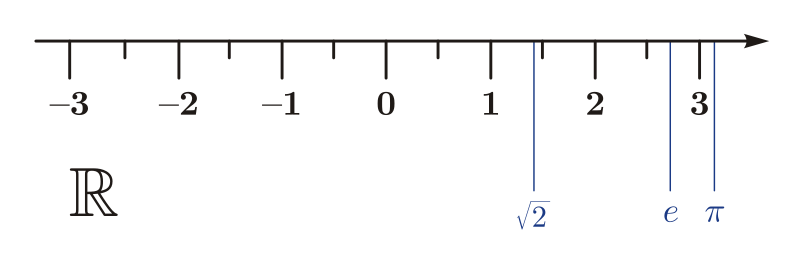

A complex number, we will first define as any number \(z\) which can be written as \(z=a+bi\) with \(a\) and \(b\) as real numbers. We’re all familiar with the real numbers, these are any number that you might see in everyday math: integers, fractions, decimals, irrationals such as \(\sqrt{2}\) and the famous values \(\pi\) or \(\phi\).

In mathy notation, this can be written as the following:

\[z \in \mathbb{C} \iff (\exists \space a,b\in\mathbb{R}) \space z=a+bi\]

This may look confusing, but in plain English this reads:

”\(z\) is a complex number provided (if and only if) there exists real numbers \(a\) and \(b\) such that \(z=a+bi\)”

This is the same definition as before.

Here you might wonder what this \(i\) figure is, and why it’s important enough to separate the \(a\) and \(b\) into separate values. As it happens, just about every number you could think of is a real number, until you realize that math has rules that you have to play around. One of these rules you may have been told is:

"You cannot take the square root of a negative number!"

This is true, but only when playing within the rules of the real numbers. As it turns out, in the late 1500s a mathematician was trying to create a formula for finding roots of a cubic polynomial - they were trying to find a “quadratic equation” but for polynomials of the form \(ax^{3}+bx^{2}+cx+d=0\). In their final formula, which was mathematically accurate for finding these roots, they noticed that it was possible for some input values to end up with a square root of a negative number partially through the process, and have it cancelled out in a later step.

For a long while this discovery was ignored, because surely this cannot be meaningful, it’s just a side effect of certain inputs to the formula, right? This value cannot be found anywhere on our real number line, so what would we even do with it? Where would we put it?

This is where \(i\) comes in, the imaginary unit. When we started taking this square root of a negative seriously, we simply defined it to be \(i=\sqrt{-1}\), of which all square roots of negatives are multiples of, and a whole bunch of interesting things started happening, including discoveries with very real applications all around us today. To this day, the field of Complex Analysis remains an actively taught and researched math field, centered around this idea of \(i\).

Note: All square roots of negative numbers are multiples of \(i\). Ex: \[\sqrt{-5}=\sqrt{-1 \times 5}=\sqrt{-1}\times\sqrt{5}=i\sqrt{5}\] with \(\sqrt{5}\) being a real number.

Side Note: I despise the use of the term “imaginary” used to describe these values. I would much prefer something like “transcendental” to describe how this value does not fit into our usual real numbers. Unfortunately, transcendental numbers already mean something else and “imaginary” has become the accepted term, so we will continue to use it here.

Graphing Complex Numbers

As mentioned above, we can see that the imaginary unit cannot be found anywhere on this real number line, since we can’t have a real number multiplied by itself to equal \(-1\). Two positive real numbers multiply to a positive number, and two negative real numbers also multiply to a positive number. This is why the parabola representing \(y=x^{2}\) never goes below the x-axis (and therefore never reaches \(y=-1\)).

However, we notice that a value can contain both a purely real component and a imaginary component, dividing this new form of number into 2 dimensions. This 2-dimensional number is what we call a complex number as defined above.

Note: Any number that is either purely real or purely a multiple of the imaginary unit (ex: \(7.5\), \(4i\), \(0\)) is still a complex number as either the \(a\) or \(b\) (or both) in \(a+bi\) can be the real number \(0\).

To represent real valued numbers we can plot them on a 1-dimensional line like the one seen just above. For complex numbers we can do a similar thing, using a 2-dimensional plane to show both real and imaginary components.

Be sure that this system of displaying complex numbers on the complex plane makes sense to you, because I will be using it extensively moving forward.

Note: In this representation, you can think of a complex number \(z=x+yi\) as having “\(x\) and \(y\) coordinates” on a standard cartesian xy-plot. The point on the image above would be represented on an xy-plot as \((3, 4)\), so on the complex plane it is shown by \(3 + 4i\). Using this was actually the key way of thinking for solving a homework problem in one of my math classes my sophomore year. For the more experienced, the problem was, with regards to Group Theory:

\[Prove \quad \mathbb{C}\cong \mathbb{R}^{2}\]

Multiplying by \(i\)

We can do algebra on complex numbers in similar ways that we can with purely real numbers. Using the definition of \(i\), we can use some algebra to deduce a few things:

\[i^{0} = 1\] \[i^{1} = i\] \[i^{2} = (\sqrt{-1})^{2} = -1\] \[i^{3} = i \times i^{2} = i \times -1 = -i\] \[i^{4} = i \times i^{3} = i \times -i = -(i^{2}) = -(-1) = 1\] \[i^{5} = i \times i^{4} = i \times 1 = i\]

From here you’d notice that the values of \(i^{n}\) cycle between \(\{1, i, -1, -i\}\) when \(n\) is an integer . This is in fact the first problem that was posed at the beginning of this article.

\[z=i^{n}, \space n \in \mathbb{Z}\]

\(n \in \mathbb{Z}\) means “\(n\) is an element of the set of integers.”

As an evaluation of this expression, a “solution” could be to state that \(z\) cycles between the values above, depending on the value of \(n\). Whenever \(n\) is a multiple of 4, \(z\) will be \(1\). If \(n\) is one more than a multiple of 4, \(z\) is \(i\), and so on.

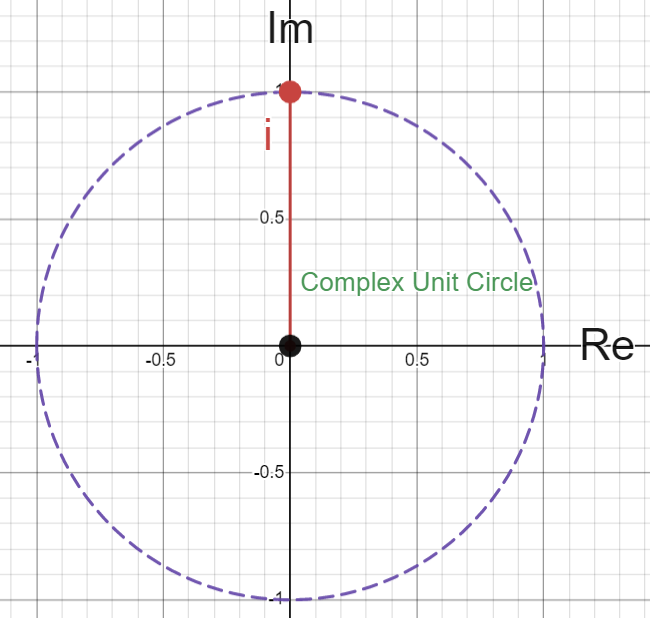

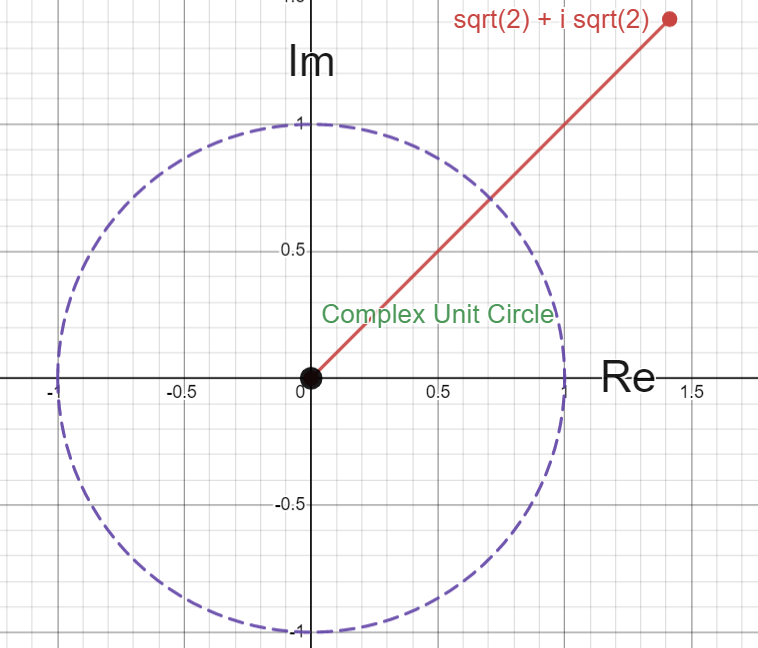

This is a fun pattern to notice, but if you plot these values on the complex plane and see them changing over time, I hope you’d notice there’s something deeper at play here. In this and following plots, the real axis is denoted horizontally as ‘Re’ and the imaginary axis is denoted vertically by ‘Im’:

Each time we multiply by \(i\), it seems we’re “rotating” whatever the previous value was by \(90^{\circ}\), or \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) radians (we will use radians from now on) counter-clockwise. The key discovery here is to see multiplication a bit differently here, not just as a stretching but more of a rotation. More importantly, it almost seems like we are tracing out the outline of a circle by rotating around.

Multplying on the Complex Unit Circle

In fact, that’s exactly what we’re doing. Analogous to how we can use polar coordinates \((r, \theta)\) as a different representation of \((x, y)\) coordinates, we can use the distance a complex number is away from zero \((r)\) and the angle it makes with the positive real axis \((\theta)\) to describe complex numbers instead of \(a+bi\).

From here on I will use the terms “radius” or “length” of a complex number to represent its distance away from \(0\). Similarly when I say “angle” of a complex number, this refers to the angle made between the positive real axis and the line from the origin to the complex value.

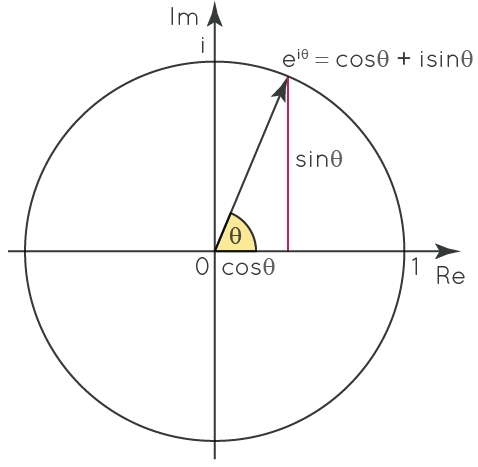

For example, you can see from the visual above that the complex number \(i\) has radius \(1\) and angle \(\frac{\pi}{2}\).

The reason we would want to do this is to be able to more closely study this cyclic property that is inherent to the way we define the imaginary unit. The way this actually looks in practice, is through one of the most fundamental formulas in all of mathematics. Discovered by Leonhard Euler and hence named after him, “Euler’s formula” states that for any complex number with radius \(1\) and angle \(\theta\):

\[e^{i\theta} = cos(\theta) + i \space sin(\theta)\]

Where e is Euler’s Constant. I’ve hidden the \(r\) from here for now. We will get back to that later.

If you don’t see the hidden circle in this formula yet, remember that \(cos(\theta)\) gives the x-coordinate of a point on the unit circle at angle \(\theta\), and \(sin(\theta)\) does the same for the y-coordinate. So here we have an expression that encodes this wild \(e^{i\theta}\) into \(x+yi\) like we saw before!

Side Note: This can easily be scaled by showing \(re^{i\theta}=r(cos(\theta)+i \space sin(\theta))\) as both real and imaginary axes are scaled proportionally, more on this later. On many modern graphing calculators, if you go into the settings two of the available modes show “\(a+bi\)” and “\(re^{i\theta}\)” as ways to represent complex values!

So what this formula is telling us is, given an angle \(\theta\), the corresponding value \(e^{i\theta}\) is going to be the value on the complex unit circle (circle centered at the origin with radius 1) whose angle is \(\theta\). For a specific example, many students in their algebra classes learn to memorize specific trigonometric values, which generally include \(cos(\frac{\pi}{3})=\frac{1}{2}\) and \(sin(\frac{\pi}{3})=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\). Using these values we can deduce that \(e^{i\frac{\pi}{3}}\) is equivalently represented by the point on the complex plane located \(\frac{1}{2}\) units to the right along the real axis and \(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) units up along the imaginary axis, labeled at \(\frac{1}{2}+i\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\).

This image below shows this visually, where the point at the end of the arrow is the value represented by the formula:

I really encourage the reader to sit on this for a bit and perhaps do a bit of research on this if they are interested. I mean it when I say that this is one of the most fundamental discoveries to all of modern mathematics, with countless applications since its inception.

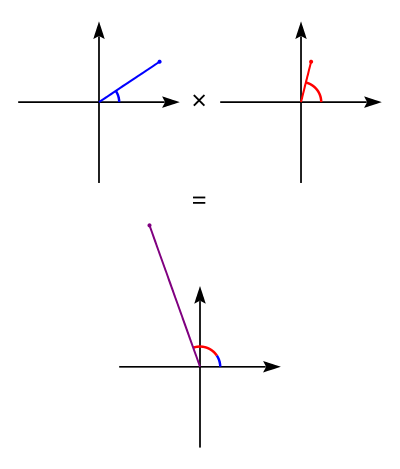

Using this form to represent values further strengthens the idea that multiplying complex numbers acts as a rotation, and we can prove this very easily.

Let’s take two numbers lying on the complex unit circle, \(z_{1}\) and \(z_{2}\), and multiply them.

We know we can represent them both using the angles they make with the positive real axis, in the form shown by Euler’s Formula, so lets say \(z_{1}=e^{i\theta_{1}}\) and \(z_{2}=e^{i\theta_{2}}\) where \(\theta_{1}\) represents the angle that \(z_{1}\) makes with the positive real axis, and \(\theta_{2}\) defined similarly. Now we can do the following with a simple algebra trick:

\[z_{1} \times z_{2} = e^{i\theta_{1}} \times e^{i\theta_{2}}\] \[= e^{(i\theta_{1}) + (i\theta_{2})} = e^{i(\theta_{1} + \theta_{2})}\]

And this is also in the form from Euler’s Formula, denoting the point on the complex unit circle with angle \(\theta_{1}+\theta_{2}\)!

So what happened here is we took two points on this circle, and when we multiplied them the resulting point was placed on the circle at the sum of the angles of the two individual points. This image displays this well. For now, disregard the radii of the values and only take note of the angles (for the curious, clicking on the image will also introduce you to a really cool thing we call the roots of unity):

It should be noted that, in our previous endeavor, we could have done the following:

\[z_{1}=a_{1}+ib_{1}; \quad\quad z_{2}=a_{2}+ib_{2};\] \[z_{1} \times z_{2} = (a_{1}+ib_{1}) \times (a_{2}+ib_{2})\] \[=a_{1}a_{2} + ia_{1}b_{2} + ia_{2}b_{1} + i^{2}b_{1}b_{2}\] \[=(a_{1}a_{2} - b_{1}b_{2}) + i(a_{1}b_{2} + a_{2}b_{1})\]

And while this would be mathematically accurate, it loses the connection to the hidden rotations that are going on behind the scenes. Plus I personally feel it is a less elegant and less satisfying conclusion.

Leaving the Complex Unit Circle

I hinted that the radii of two multiplied complex numbers must be 1 for this to work, which is not fully true. This can easily be scaled by showing \(r_{1}e^{i\theta_{1}} \times r_{2}e^{i\theta_{2}} = (r_{1}r_{2})e^{i(\theta_{1} + \theta_{2})}\). What this means is that, to multiply any two complex numbers, the resulting number will have length that is equal to the product of the first two lengths, and angle that is the sum of the first two lengths as we just learned. The animation below shows this well, with the red value showing the product of the green and blue values. This is truly the essence of what I hope to have shown in this post. Thinking on this principle will lead you to discover just how meaningful this complex unit circle is in its relation to scaling values and will allow for a different thought process to approaching problems.

As a side effect of this formula, plugging in \(\pi\) gives us \(e^{i\pi}=-1\) and thus \(e^{i\pi}+1=0\). This has come to be known as Euler’s Identity or, more commonly, The Most Beautiful Equation in Mathematics.

And that’s the second question I posed at the start of this post! Really well done if you’ve made it this far. Now it’s time for the real good stuff. At this point we’ve built all the intuition we need to start solving some numeric problems in a very special way.

Solving Complex Problems

Problem 3

Lets take a look at the third problem I posed: \(z=\sqrt{i}\)

This problem was inspired by this video made by one of my favorite math channels. In this video this problem was approached in a very algebraic way. This is mathematically valid and produced the correct answer, but in my opinion this puzzle has a much better solution visually, which we will explore here.

As promised, we already have all of the tools that we need to find an algebraic expression for \(z\).

Lets take a look at what it means to take the square root of something. When looking for the square root of \(i\), we are really looking for some value that, when multiplied by itself, equals \(i\).

Well we previously built up the intuition for multiplying complex numbers, so now all we need to do is find this value that fits this criterion.

We know that \(i\) lies at the very top of the complex unit circle, so we can deduce a few things like we did before: that the radius of \(i\) is 1, and the angle it makes with the positive real axis is \(\frac{\pi}{2}\). This means we can write \(i\) as \(1 \times e^{i\frac{\pi}{2}}\) (some call this the polar representation of \(i\))

So now we need to find \(r\) and \(\theta\) for \(z=re^{i\theta}\) such that \(z^{2}=i\). This means:

\(z^{2}=(r \times r)e^{i(\theta + \theta)}=r^{2}e^{2i\theta}\quad\) is the same as \(\quad i=1 \times e^{i\frac{\pi}{2}}\)

So \(r^{2}e^{2i\theta}=e^{i\frac{\pi}{2}}\)

Since this \(r^{2}\) determines the radius of the resulting value which has to be \(1\), we know \(r\) must also be \(1\).* And from here we can also see that \(2\theta = \frac{\pi}{2} \implies \theta = \frac{\pi}{4}\)

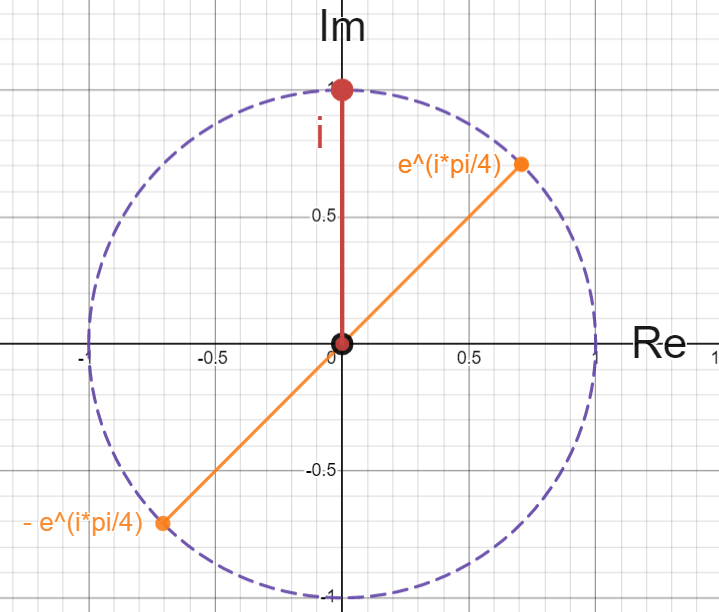

And this is our solution! \(e^{i\frac{\pi}{4}}\)

This was still an algebraic solution, but looking at the image should convince you of why this point lies halfway up the complex unit circle between \(i\) and the positive real axis. This is because squaring a complex number doubles its angle, which in this case lands us directly on \(i\). This is really all the information needed to have solved this purely visually.

*if you want to say r could be -1, you’d be correct! Try to convince yourself visually why \(-e^{\frac{i\pi}{4}}\) is also a solution to this problem.

Problem 4

\(z=(\sqrt{2} + i\sqrt{2})^{4}\)

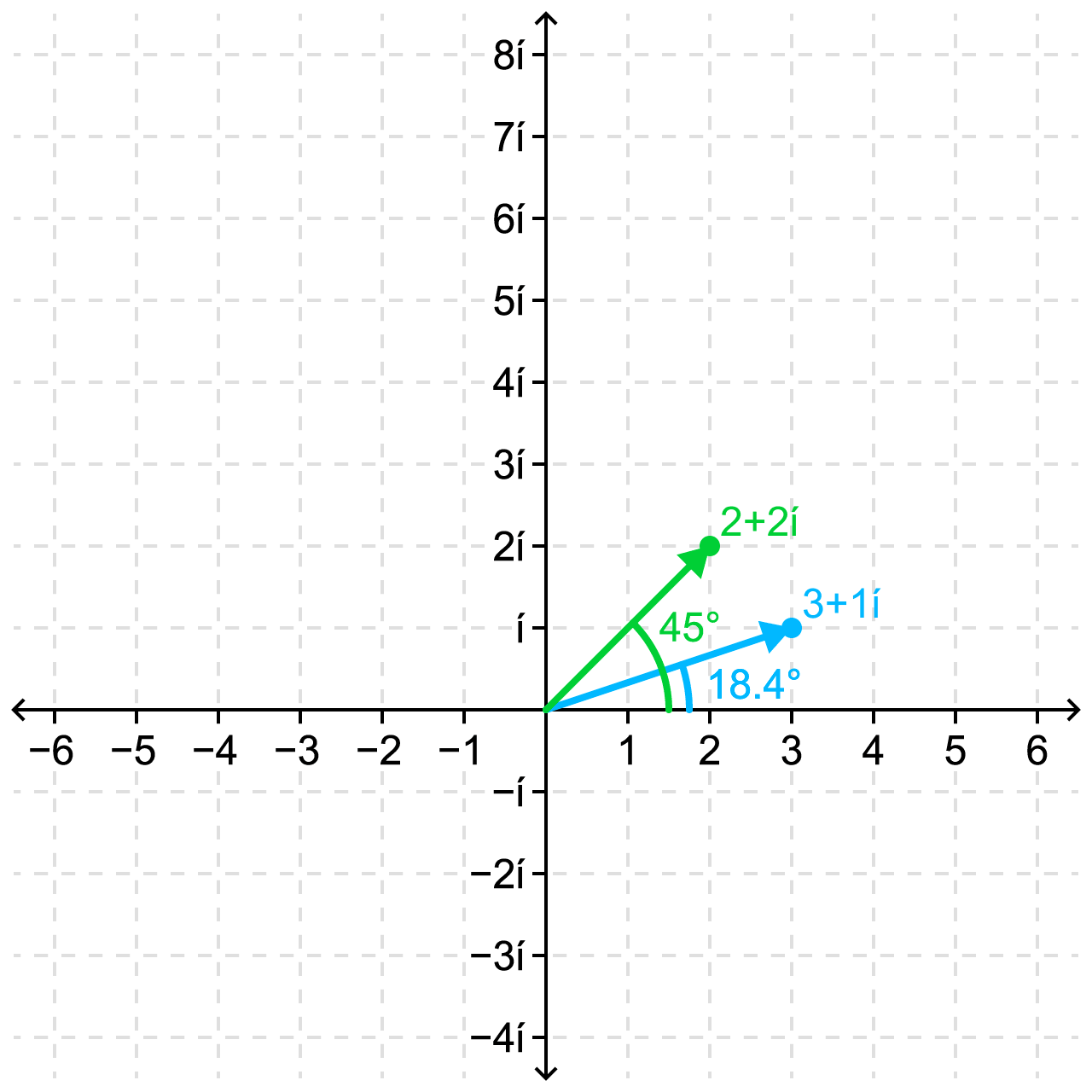

Finding where this value ends up is a little more nuanced than the last problem, but again if we follow the same rules that we’ve developed we can solve this one too. This particular problem is one that can be solved without too much trouble by expanding out our expression and multiplying through a couple times. However I hope by this point you would prefer to tackle this one from a more geometric point of view. This would make this puzzle more elegant and satisfying to complete.

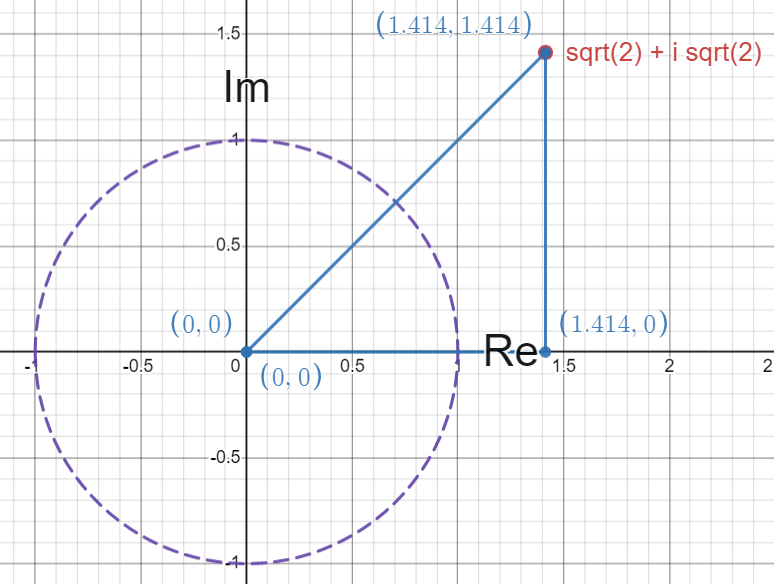

I encourage you to look at the image below, and first try to reason through the steps you might take to solve this problem yourself.

The first thing you may notice is that this \(\sqrt{2} + i\sqrt{2}\) value lies outside of our familiar complex unit circle, meaning its radius is greater than 1. What this also means is that when we multiply this number by itself, also a number with radius greater than 1, its resulting length is going to increase. This is why the complex unit circle is so important, similar to how real numbers greater than 1 and less than -1 make the magnitude of other real numbers larger when multiplied.

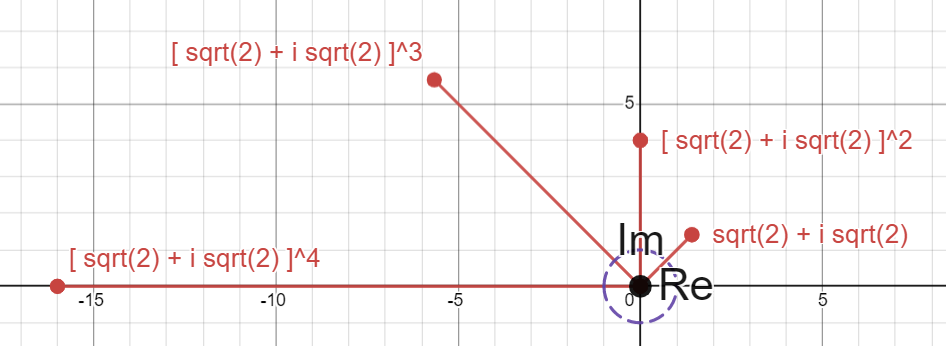

Another thing you may realize is that, since the real and imaginary components of this number are equivalent, this value has an angle of \(\frac{\pi}{4}\) with respect to the positive real axis, or \(45^{\circ}\). This could also be found using some sneaky trig, similar to how we find the radius of this number below. Since we know this starting angle of \(\frac{\pi}{4}\), we can also reason that after multiplying this number 4 times, the final angle of \(z\) will be \(\frac{\pi}{4}+\frac{\pi}{4}+\frac{\pi}{4}+\frac{\pi}{4}=\pi\) as each time we multiply this number by itself, we are rotating it another \(\frac{\pi}{4}\) radians. This clues us in that the final answer will be a strictly real, negative number, as the negative real axis lies at angle \(\pi\) on the complex plane!

So now that we know the final angle of \(z\), we need to find the magnitude of this result. As mentioned before, when we multiply complex numbers, the resulting value has a length that is a product of the two original lengths. In this case where we are multiplying a number by itself 4 times, we know the final length of \(z\) will be the initial length of our \(\sqrt{2}+i\sqrt{2}\) raised to the fourth power.

To find this length, we only need to utilize a very well known geometric theorem - the Pythagorean Theorem. If we divide this value into its real and imaginary components, we see this triangle emerge.

Each of the legs of this right triangle has length \(\sqrt{2}\), and so the length of the hypotenuse, which is the length of our \(\sqrt{2}+i\sqrt{2}\), must be \(2\).

Using what we found above, we know that this means that the final magnitude of \(z\) is \(2^{4}=16\).

So now we have our final answer. \(z\) has radius \(16\) and angle \(\pi\), so therefore

\((\sqrt{2}+i\sqrt{2})^{4}=16e^{i\pi}\quad\) or more commonly \(-16\).

And that’s the answer! Below is an image that shows the repeated multiplying by our number, you’re really able to see the rotations and extensions happening here, creating a sort of spiral out from the center, which I think is really cool.

I really hope you’ve learned something here and start to see how these amazing numbers are more than just a result of weird inputs to an equation. Complex numbers and their strange and fun properties have fascinated me for quite some time, and I really enjoyed putting this together. Thanks for reading, and I’ve left some extra challenges below for the mind that needs more stretching.

Extra Challenges

Evaluate \(z=\sqrt{4(\frac{1}{2}+i\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2})}\)

Click here for the solution.

We define the conjugate of a complex number \(z=a+bi\) as \(\bar{z}=a-bi\), think of \(z\) reflected over the real axis.

These two formulas can be derived from the Taylor Series expansions of \(cos(z)\) and \(sin(z)\):

\[cos(\theta)=\frac{e^{i\theta}+e^{-i \theta}}{2}\] \[sin(\theta)=\frac{e^{i\theta}-e^{-i \theta}}{2i}\]

However there is a much easier way and more elegant way to prove these formulas. Sit on them for a while and break them down in pieces, and see if you can convince yourself visually that these are true.

Click here for my solution.

This question is taken from Brilliant’s Complex Analysis self-guided course:

For how many \(z \in \mathbb{C}\) is \(z^{2}=\bar{z}\)?

Click here for the solution.