Complex Rotations Extra Challenge 3

For how many \(z \in \mathbb{C}\) is \(z^{2}=\bar{z}\)?

Scroll Down to just see the answer.

If you aren’t familiar with the complex conjugate of a value, view the first part of Challenge 2.

To answer this question we have to think of what we are actually doing to complex values when we take the square or conjugate.

Hopefully you’re comfortable squaring complex numers as we’ve learned how to multiply two separate values - its angle will double and its radius will square. As for taking the conjugate, this is simply a reflection of the value over the real axis. So we’re looking for values that, when we square them it acts the same as performing this reflection over the real axis.

The key realization here has to do with the radii of our values. We know any solution \(z\) can be written as \(z=re^{i\theta}\). Let’s think about what happens to this radius when we perform our operations.

For any complex value \(p\), the radius of \(p\) and \(\bar{p}\) will be the same, since all we are doing is a reflection about a major axis, so the distance the value is away from \(0\) will be preserved after this action.

When we square a complex value, however, the radius does have the ability to change. If \(p\) has radius \(r_{p}\), then \(p^{2}\) has radius \(r_{p}^{2}\), as we previously learned.

This is important because, if we have \(z=re^{i\theta}\) such that \(z^{2}=\bar{z}\), this means that the radii of \(z^{2}\) and \(\bar{z}\) must be the same. Namely, we have:

\[r^{2}=r \implies r \in \{ 0, 1 \}\]

Let’s explore these. First we’ll look at \(r=0\). The only complex number that has distance \(0\) away from \(0\) is, well, \(0\). And we can see this as a trivial solution to our problem, as \(0^{2}=0=\bar{0}\).

This might raise a realization here, that when we deal with strictly real numbers \(a\), our question turns into \(a^2=a\), as \(\overline{a+0i}=a-0i=a\). This means that \(1\) is also a solution here, which we can validate.

I call these trivial solutions because they don’t fully capture the way of thinking that we need to find the rest of the solutions, because they don’t need to. These are strictly real, non-negative numbers, so squaring them doesn’t have much going on in terms of angles (\(0^{\circ} \to 0^{\circ}\)), and reflecting over the real axis has no effect at all when taking the conjugate.

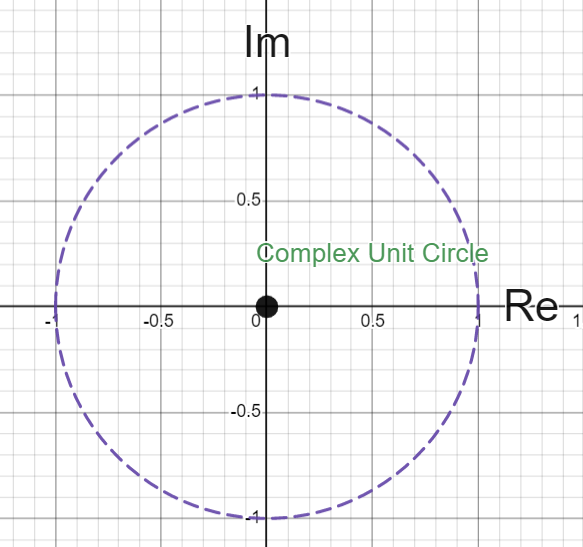

With this in mind, I encourage you to take another pause and convince yourself that there are more solutions. Start just by thinking of where they might be on the complex unit circle (we know they have radius 1 from our earlier calculation). Until you have a good idea of around where they could be on the circle, I would suggest avoiding calculating any actual values, just focus on visualizing around where they might exist.

There are multiple ways to approach this problem, and if my explanation doesn’t seem natural to you, sit on this question for a bit and try some things out that do seem more natural to you. You definitely can come up with the correct solution with a different way of thinking than I did. That being said, from here on I’ll be explaining my thought process from when I originally solved this puzzle.

When I first came across this problem, I was given a multiple choice selection screen with answer choices 1, 2, 3, and 4. The first 2 were simple enough to come up with, and I knew any non-trivial solutions had to lie on this complex circle like we deduced here, but I couldn’t put actual values to what I had in mind. I had begun to think that the only values this solution applies to are \(0\) and \(1\), but then I started thinking about the angles that could produce these solutions.

I recognized that we need these angles to be somewhere “past the imaginary axis”, angles between \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) and \(\frac{3\pi}{2}\), so that once we double the angle, the resulting angle is on the other side of the real axis.

My first thought was to try \(e^{i \frac{3\pi}{4}}\), which is \(45^{\circ}\) past the positive imaginary axis, but \(2 \times \frac{3\pi}{4} = \frac{3\pi}{2}\), which is further along the complex unit circle than the conjugate of \(e^{i \frac{3\pi}{4}}\).

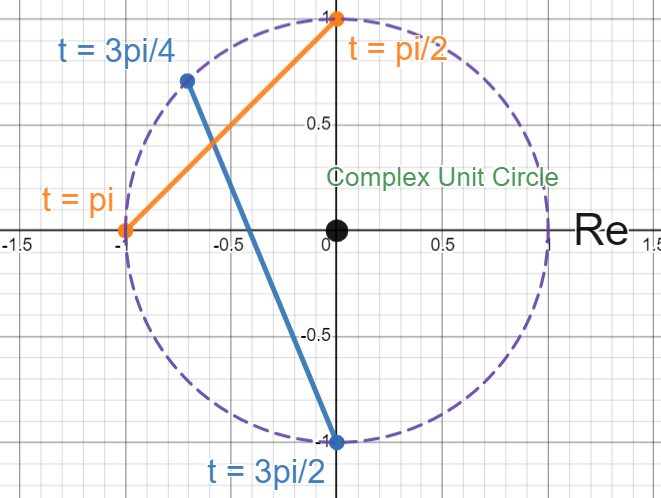

So, because I knew \(e^{i \frac{\pi}{2}}\) would yield \(2 \times \frac{\pi}{2} = \pi\) (or just by thinking of \(i^{2} = -1\)), I got the following image in my head. Here, angles made with the positive real axis are labeled as t, and both of the lines connect between the complex values I tried and their squares (after doubling the angles):

The answer we’re looking for will have a line that is purely vertical, mapping the complex value directly to its conjugate. Because of the fact that this process we are taking of doubling angles is continuous (shown by the following animation), we know by our friend the IVT that somewhere between these two lines shown above lies a vertical line.

Here, t1 refers to \(e^{i t_{1}}\) which is connected to t2, which represents \((e^{i t_{1}})^{2}\):

![]()

There’s a lot that can be unpacked from this animation. First, we confirm that whenever t1 is “past the imaginary axis”, t2 is on the opposite side of the real axis. Also we see that this verifies \(1\) as a solution, since this is technically adhering to the vertical line passing through t1 and t2 (kinda).

We can also see where t1 and t2 create a vertical line, so we know that \(e^{i t_{1}}\) is a solution to this problem for whatever value t1 actually is at this point. Interestingly enough, we see t2 is also a solution at this instant! We know this because, when t1 reaches the point where t2 was at the first vertical line, the line seems to have flipped across the real axis, creating another vertical line.

For the curious, these values are \(e^{i\frac{2\pi}{3}}\) and \(e^{i\frac{4\pi}{3}}\)

Side Challenge: Verify algebraically that, for this problem, solutions must come in conjugate pairs. This means, \(z\) is a solution implies \(\bar{z}\) is a solution.

At this point we have all that we need to state our answer! We know \(0\) and \(1\) are solutions, and then these 2 points on the unit circle are the only other places in this diagram that create a vertical line, so we have 4 values for \(z \in \mathbb{C}\) such that \(z^{2}=\bar{z}\).

Note: I didn’t actually realize that these two non-trivial solutions had to come in a conjugate pair at first. I almost selected 3 as my final answer until I realized that going the same angle in the opposite (clockwise) direction yields the same reasoning for a solution. It also wasn’t until much later when I found the actual value for this solution. Had I realized this fact about solutions coming in conjugate pairs earlier, I could’ve had a much more elegant solution using arcs going around the circle, probably coming up with a diagram similar to this, which may be how others found the solution:

![]()

Answer

For how many \(z \in \mathbb{C}\) is \(z^{2}=\bar{z}\)?

Solution Set: \(\{0, 1, e^{i\frac{2\pi}{3}}, e^{i\frac{4\pi}{3}}\}\)

So we have 4 solutions.

Click here to return to the post.

Click here to return home.