1111x1111 = 1234321

Palindromic Multiplication and Number Systems

July 1, 2022

- Multiplying by 11

- Palindromes

- Number Systems

- More Number Systems

- An Additional Problem - July 5 2022

- My Solution

Multiplying by 11

I believe I was first taught my multiplication tables in the third grade. In my class we would sometimes play a highly competitive, one on one showdown multiplication game to test our knowledge in a fun way. Two kids would stand up side by side, and the teacher would flip a flashcard with two numbers, both always between 1 and 12, and the first of the two students to correctly shout the product of these numbers would move on to face the next kid. The highest of victories belonged to one who would be able to make their way through the entire room without being beaten, a dream achieved by only one person in the whole class - Mike Gerhart. I would usually beat a handful of kids in a row, but my mental math has never been remarkably strong and I would always end up taking an early seat.

Once when we were playing this game I was having a particularly good day, and the conditions were perfect for me. The notorious mental math ace and now good friend of mine, Mike Gerhart, sat to my left after an stunning upset. I was now pitted against the one who slayed this beast. After defeating them I found myself moving around the classroom at marvelous pace, vanquishing each of my enemies one by one.

After I had conquered all but one of my adversaries, my victims now looked to me to become the second ever to make the rounds and claim my position in history as one to circle the whole room. My final battle of my campaign meant I had to face the only other to complete the task. Shaking in nervousness I stood up by Mr. Gerhart and awaited my two numbers that would either propel me into celebrity status or leave me in defeat.

I blinked my eyes at the most unopportune moment, and had a fraction less time than Mike to notice the numbers had been flipped:

\[11 \times 7\]

Before I had a chance to process this, the champ yelled out the answer to one of the easiest possible number pairs one could ask for, and my peers roared in anguish as I was forced to join them in defeat, never to achieve this massive goal of mine.

Everybody in that room knew their 11’s multiples, at least up until \(11 \times 11\), because all it does is “double” whatever number it’s multiplied with. \(11 \times 11\) is where it gets interesting. \(11 \times 11\) was easy to remember, because it was just “one two one.” Simple, right?

Here we’re going to explore the interesting pattern that arises when you dig a little deeper into this idea.

Palindromes from 111, 1111

Later in that same year, in that same classroom, I found myself doing what I’m sure all of us have done at some point - playing with my calculator. This wasn’t some fancy calculator with lines and graphs and, ugh, statistics, this was a four function calculator with the small “solar panel” strip that you could cover with your thumb to make the digits disappear from the display.

I was haphazardly inputting different operations when I came upon this pattern:

\[111 \times 111 = 12321\] \[1111 \times 1111 = 1234321\]

I didn’t know what a palindrome was at the time, but I did notice that these products seemed to be counting from 1, up to a number and then back down to 1 on the other side.

I kept going with this until I realized this pattern broke once I inputted a string of 10 1’s in a row. The calculator I was using probably showed this in scientific notation (which I didn’t know what it meant for a long time, my brother and I legitimately used to say “\(1.3e24\)” as “one point three, Eistein’s Theories, twenty four”), but I was still able to notice the pattern didn’t follow the “12345…” and back down idea.

Let’s take a closer look at what we’re doing when we multiply these strings of ones together. For now we’ll be working in our usual base 10 decimal system, but we’ll expand this later.

Let’s start out with just \(111 \times 111\). To multiply these, we can break these numbers down in the following way:

\[111 \times 111 = (100 + 10 + 1) \times 111\]

\[= 11100 + 1110 + 111 = 12321\]

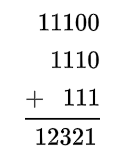

This last step can be shown vertically like this:

Notice how, when we multiplied a string of three 1’s by itself we got an addition of three values, each with three ones, offset by 0, 1, and 2 zeroes.

Let’s move a step up now:

\[1111 \times 1111 = (1000 + 100 + 10 + 1) \times 1111\]

\[= 1111000 + 111100 + 11110 + 1111 = 1234321\]

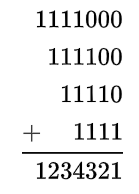

Which can be seen as:

Here we have a string of four 1’s multiplied by itself to get an addition of four values, each with four ones, offset by 0, 1, 2, and 3 zeroes.

Number Systems

Now we have a better idea of what’s going on here when we perform these calculations, so let’s try and generalize this idea that we found above.

We can say based on this pattern, that if we have a string of \(n\) 1’s in a row multiplied by itself, we will get an addition of \(n\) values, each with \(n\) ones, offset by 0, 1, 2, …, \(n-1\) zeroes. This will result in a value that looks like the following:

\[1 \space 2 \space 3 \space … \space n-1 \quad n \quad n-1 \space … \space 1\]

But consider the case that originally stumped me:

\[1111111111 \times 1111111111\]

This doesn’t follow our formula, because from the left we see “…5679…” and it seems to skip over the 8. So where does our formula fall apart?

As a matter of fact, it doesn’t!

Our formula actually works perfectly fine, but we need to impose one more condition: that we need to be operating on numbers in a number system with base greater than \(n\).

If you’re not familiar with how number systems work, check out this good article here

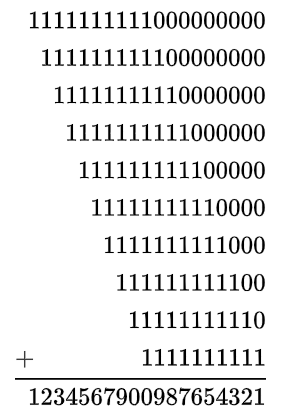

Take another look at the image above. If we instead counted the amount of ones in each column of our answer we would get something like this, where “|” here is being used to denote the different place values of our answer:

1111111111 x 1111111111 =

|1|2|3|4|5|6|7|8|9|10|9|8|7|6|5|4|3|2|1|

This follows our generalized formula as we expect, and here we start to see why this formula fails to work for this value when viewed in a base 10 number system, because when we sum up 10 ones as we did in that middle column, we are all taught to “carry the 1” to the next place value. If we do this with the boxes we’ve created above we’d see we get the same “…5679…” number that we arrived at before.

To avoid this carrying over, we just need to view this number in a different number system*. Using a number system with base greater than \(n\) ensures that when we reach the \(n\) in the very middle of our pattern, we have a symbol to represent it and therefore do not have to “carry the 1” to the next place value.

*Yes, I know this changes the actual value of the number in question. The point of doing this is for the purpose of extending our pattern we found and explaining why we might assume it fails to works once you reach a certain point. If you’re asked to evaluate 1111111111x1111111111 in base 10 in your daily life, you’re out of luck in using this technique.

More Number Systems!

What this means is that this fun pattern will arise in any number system! We also can predict exactly when this pattern will “break down” in that number system. We know that, since we need to use a number system with base greater than \(n\) for this pattern to hold, it will break down once we try to multiply a number with \(n\) ones by itself in that number system.

So in base 4, this will break down when we try 1111x1111. From here we will use subscripts of numbers (in decimal of course) to denote which number system we are using. If no subscript is given, it is implied the value is represented in base 10 notation:

\[11_{4} \times 11_{4} = 121_{4}\]

\[111_{4} \times 111_{4} = 12321_{4}\]

\[1111_{4} \times 1111_{4} = |1|2|3|4|3|2|1|_{4} = 1300321_{4}\]

These expressions are equivalent to the following in decimal (the base 10 number system we all just love so much for some reason):

\[5_{10} \times 5_{10} = 25_{10}\]

\[21_{10} \times 21_{10} = 441_{10}\]

\[85_{10} \times 85_{10} = 7225_{10}\]

This fact that we can predict how the pattern will behave in a certain number system is fun, but I think the coolest takeaway from this idea that this pattern holds in any number system that is greater than the amount of ones we have. For example, \(1111_{8} \times 1111_{8} = 1234321_{8}\) in the same way that \(1111_{9} \times 1111_{9} = 1234321_{9}\), \(1111_{10} \times 1111_{10} = 1234321_{10}\), and \(1111_{j} \times 1111_{j} = 1234321_{j} \space ; \quad \forall j \gt 4\)!

Here’s that example:

\[1111_{8} \times 1111_{8} = 1234321_{8}\]

\[1111_{9} \times 1111_{9} = 1234321_{9}\]

\[1111_{10} \times 1111_{10} = 1234321_{10}\]

Which correspond to:

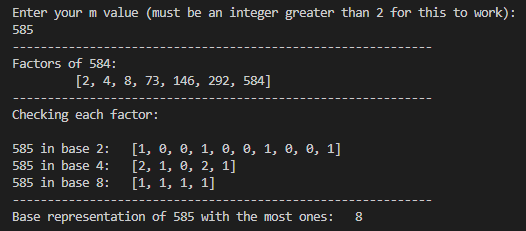

\[585_{10} \times 585_{10} = 342225_{10}\]

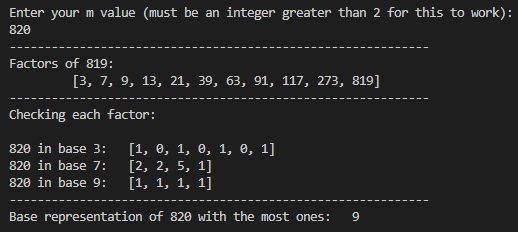

\[820_{10} \times 820_{10} = 672400_{10}\]

\[1111_{10} \times 1111_{10} = 1234321_{10}\]

These are three completely different expressions, yet can be shown by the same pattern in their different number systems. Isn’t that cool?

I’m sure there’s more to be explored with this, but this is all that my mind takes me to with this. Let me know what more there is the be discovered!

Addendum - July 5, 2022

From this point on in the post is just me proposing and thinking through an additional problem that came into my mind when writing this. The number theorist among you will most likely enjoy thinking through this with me.

Also from here on, we will be disregarding the unary number system, because it doesn’t follow the same rules as any other number system, plus it gives a really unsatisfying view of our problem. For our intents and purposes moving forward, base-1 does not exist.

Seeing this example above, translating \(585_{10}\) and \(820_{10}\) into base 8 and 9 such that their representations in these number systems are strings strictly of ones got me thinking, what makes these numbers special in base 10? What other numbers do we have in decimal that we can translate into another number system such that it’s representation in that number system is just ones?

Well, I realized that for all integers \(m \gt 2\) (ponder for a moment why I make this distinction), we can construct this string using base \(m-1\). This is true because the representation of \(m\) in base \(m-1\) will always be \(11\). Convince yourself of this briefly.

Ok so that’s cool, we can take any \(m\) and make it into a string of ones, \(11_{m-1}\), and from there we can say that \(11_{m-1} \times 11_{m-1} = 121_{m-1}\) (This expression is now under the assumption \(m \gt 3\)).

But take another look at the example we had before. It’s not like we just took \(585_{10}\) and said \(11_{584} \times 11_{584} = 121_{584}\), this way of approaching this isn’t really that meaningful and is pretty unsatisfying if you ask me. I would say that, in the way we said \(585_{10}\) and \(820_{10}\) are special in decimal, I would argue that, the more ones we can have in the string of numbers (ex: \(585_{10}\) as \(1111_{8}\) rather than \(11_{584}\)) makes the number more special.

Let’s make this more rigorous: take a number \(m \in \mathbb{Z}\) by \(m \gt 2\). I’ll denote this moving forward as \(m \in \mathbb{Z}^{\gt 2}\).

Define the Unity Base of m, \(\gamma_{m}\), as the base of the number system in which the representation of m contains only ones, and the most quantity of ones when compared to other bases.

Define the Unity Index of m, \(\epsilon_{m}\), as the number of ones that are present in \(\gamma_{m}\).

Define the Unity Base Set of m, \(N_m = \{a \in \mathbb{Z}^{\ge 2} : m_{a} \space contains \space all \space ones\}\). This means that \(N_{m}\) will contain all of the decimal numbers of the bases in which \(m\) represented in that base contains only ones.

For example:

It can be shown by exhaustion that \(\gamma_{15} = 2\) as \(15_{10}\) contains only ones when represented in binary (base 2) and this representation contains the most ones out of any other number system base to choose from. Also, \(\epsilon_{15} = 4\) as \(15_{10} = 1111_{2}\) which has 4 ones. Further, \(N_{15} = \{2, 14\}\) as \(15_{10} = 1111_{2} = 11_{14}\)

I made these terms up for the sake of this problem, I don’t think these are real things in the math world ( yet :) ). The reason I’m putting definitions to these is that there are plenty of other problems that can be made from this line of thinking, such as digging into the spaces between values within \(N_{m}\) (my intuition tells me that it will never contain values above \(\frac{m}{2}\) apart from \(m-1\)) or the intersections of these Unity Base Sets and what properties they give about the numbers themselves. I haven’t put much thought into these yet but I’m sure there are discoveries to be made here.

It can be noted that for any \(m \in \mathbb{Z}^{\gt 2}\), \(\epsilon_{m} \ge 2\) as \(m\) can always be represented by \(11_{m-1}\) from before. We can also say for this reason that \(|N_{m}| \ge 1\), and more importantly \(N_{m} \ne \emptyset\).

From what I said earlier, my claim is that the greater \(\epsilon_{m}\), the more special the number feels to me. What we’re really trying to do here is trying to find \(\gamma_{m}\) as this is the base system in which \(m\) can be represented by the most ones (\(\epsilon_{m}\)).

One could say here, “well that just means we can make these special numbers by taking 1111111… from base 10, just keep adding ones!” This is true, yet I would call this the trivial approach to this problem (and hence less special to me). The real beauty of this problem, in my opinion, comes from looking at these values, not by constructing them from any given number system, and not even as the set of values themselves, but with respect to the larger integer number line and seeing them pop up in unlikely places.

Why do we think prime numbers are interesting? It isn’t just because of the numbers themselves having only 2 factors, to really appreciate the mystery of prime numbers you have to look at them as a seemingly sparse overlayment of the natural numbers. Looking at prime numbers in this way opens up a ton of new problems and ways of thinking, such as the long-standing unproven Twin Prime Conjecture or my favorite 3b1b video. I believe that seeing these kinds of numbers in the same way we can view prime numbers sheds a much more elegant light on the problem.

I think a cool graphic to add to this post would be a xy-plot bar graph with x showing the natural numbers and the y axis having \(\epsilon_{x}\) for each x. Or even a x, \(\gamma_{x}\) plot for that matter. I might try to make that at some point in the future.

Now that we have these definitions in order, we can ask the central question to this discussion:

Given \(x \in \mathbb{Z}^{\gt 2}\), what is \(\gamma_{x}\)?

In other words, how could we go backwards from \(585_{10}\) to know that 8 is the best base for representing this value in all ones? (For those wondering, I checked 2-7 and none of them show all ones)

Another way to look at this that seems like it might have a combinatorial/generating functions angle is:

Given \(x \in \mathbb{Z}^{\gt 2}\), what is the value for \(h \in \mathbb{Z}^{\ge 2}\) such that \(n\) is maximized:

\[x=\sum_{i=0}^{n}h^{i}\]

Here, \(n\) would end up being \(\epsilon_{x} - 1\), but of course this value is unknown at the point of creating this expression for a given \(x\).

An Algorithmic Solution

I’ve never gone much into a number theory problem such as this one, so here’s a brain dump of some of my thoughts:

When we represent a number \(m\) with all ones, this means that \(m\) is one greater than a multiple of whatever base we’re in. Convince yourself of this if you’re uncertain.

This means that if \(m\) is one more than a prime number then \(|N_{m}| = 1\), which also means \(\gamma_{m} = m - 1\) in this instance. Not terribly relevant but interesting nonetheless.

Another very important realization comes with looking at what happens when we look at numbers in increasing number system base. We should notice that, as we go from \(m_{b}\) to \(m_{b+1}\) with an arbitrary \(b \in \mathbb{Z}^{\ge 2}\), one of two things can happen.

Firstly, \(m_{b+1}\) may have less place values filled than \(m_{b}\). As an example, \(17_{10} = 101_{4}\) while \(17_{10} = 32_{5}\), notice how when we move from base 4 to 5, we “lose a place value” in our representation.

If this doesn’t happen, \(m_{b+1}\) must have the same amount of place values filled as \(m_{b}\). An example of this being \(15_{10} = 33_{4} = 30_{5}\) with representations in base 4 and 5 both having 2 “filled” place values. \(m_{b+1}\) cannot have more digits than \(m_{b}\) because each digit of the number represented in base \(b+1\) accounts for more of the total value of \(m\) than it would in base \(b\).

We can take this case by case.

Lets start by knocking out that second case, where \(m_{b}\) and \(m_{b+1}\) have the same amount of digits. Let’s assume for now that \(b = \gamma_{m}\), meaning \(b \in N_{m}\) and so \(m_{b}\) has all ones, \(\epsilon_{m}\) amount of ones. We also know for this case that \(m_{b+1}\) has \(\epsilon_{m}\) digits. If we can show that \(b+1 \notin N_{m}\), this means that of all of the bases that have \(\epsilon_{m}\) digits in their representation of \(m\), none of them are composed of all ones except for \(b\) (to show this generally instead of just the +1 case, we would simply replace the 1 in \(b+1\) with an arbitrary natural number \(x\) and everything moving forward is the same. Note that this is still under the assumption that \(m_{b}\) and \(m_{b+x}\) have the same number of digits). This means that, if we find a representation of \(m\) that has all ones in a certain base, we don’t have to check if the representation of \(m\) has all ones in any number system of larger base (remember, we’re trying to find the number system base that has the most ones in its representation of \(m\)). This statement has a subtlety implied based on how number systems operate that is covered in the next case.

This is actually very easy to show by contradiction. If we assume that \(b+1 \in N_{m}\), based on our assumption for this second case that \(m_{b}\) and \(m_{b+1}\) have the same amount of digits we can say:

\[m=\sum_{i=0}^{\epsilon_{m} - 1}b^{i}=\sum_{i=0}^{\epsilon_{m} - 1}(b+1)^{i}\]

If we break this apart:

\[b^{0} + b^{1} + … + b^{\epsilon_{m} - 1} = \]

\[(b+1)^{0} + (b+1)^{1} + … + (b+1)^{\epsilon_{m} - 1}\]

We can see that each of the terms, apart from the first, on the bottom expression must be larger than the respective terms on the top expression, meaning that

\[\sum_{i=0}^{\epsilon_{m} - 1}b^{i} \lt \sum_{i=0}^{\epsilon_{m} - 1}(b+1)^{i}\]

Which is a contradiction because based on our assumption they must be equal. What this means is that our original assumption must be false, which means \(b+1 \notin N_{m}\)! Breathe a sigh of relief, this makes our heuristic much simpler.

From here we can consider the first case we mentioned. This one is simple - assume \(b, \space b+1 \in N_{m}\). For this case \(m_{b}\) has more digits than \(m_{b+1}\). This is all the information we need to conclude that we can disregard \(m_{b+1}\). Even though it has all ones, we know that \(m_{b}\) has more ones.

Side note: I understand we haven’t actually covered all of the cases mentioned here. Ex: what if \(m_{b}\) has more digits than \(m_{b+1}\) but \(b \ne \gamma_{m}\)? This and all of the other cases we could mention can either be disregarded on account of irrelevance (\(b, \space b + x \notin N_{m}\)) or they can be boiled down to the same kind of argument with a slightly different assumption than above. The remaining conclusion as will be presented will be the same

Putting this back together, we actually have everything we need to come up with a very reasonable algorithm for finding \(\gamma_{m}\). Our steps above show us that

\[\gamma_{m} = min(N_{m})\]

But we don’t actually know the values in this \(N_{m}\) set yet without checking them all, so we need to do more to arrive at an actual numeric answer. First off, we know from earlier \(\gamma_{m}\) divides \(m-1\), so we can start by listing all of the factors of \(m-1\) starting from 2. I think we can also remove from this list every number that is greater than \(\frac{m}{2}\) and less than \(m-1\), but again that’s just my intuition talking and I haven’t figured out a way to show this is true yet, it very well could be false.

So now we have a list of factors of \(m-1\) excluding 1, lets call this \(F_{m-1}\)*. Now we can start with the least value of this list and look at \(m\) represented in this base. If it has all ones, then we’ve found \(\gamma_{m}\), and if not we move on to the next higher value in the list, continuing in this way until we’ve found the least value in \(N_{m}\).

*A cool note is that, we’ve already shown at the start that \(N_{m} \subseteq F_{m-1}\). Another thing to ponder is: what values of \(m\) cause \(N_{m} = F_{m-1}\)? My intuition is that it’s just the numbers 1 more than a prime number? Food for thought!

I’ve quickly coded this algorithm up in python, located here. Notice how, when we input 585 and 820 like we had before, we get 8 and 9 like we expect.

Additionally, I wrote some really sloppy code to see all of the cool numbers from 3 to 100001, (any number represented by 5 or more ones in some base) which is commented out in the script above. Here’s what I got, where each set of numbers is value:base

{31: 2, 63: 2, 121: 3, 127: 2, 255: 2, 341: 4, 364: 3, 511: 2, 781: 5, 1023: 2, 1093: 3, 1365: 4, 1555: 6, 2047: 2, 2801: 7, 3280: 3, 3906: 5, 4095: 2, 4681: 8, 5461: 4, 7381: 9, 8191: 2, 9331: 6, 9841: 3, 11111: 10, 16105: 11, 16383: 2, 19531: 5, 19608: 7, 21845: 4, 22621: 12, 29524: 3, 30941: 13, 32767: 2, 37449: 8, 41371: 14, 54241: 15, 55987: 6, 65535: 2, 66430: 9, 69905: 16, 87381: 4, 88573: 3, 88741: 17, 97656: 5}

It should be noted that, if we’re trying to do this for the purpose of using our pattern that we discovered earlier in the main portion of the post, we need to consider whether our base is large enough to hold the values when multiplied by itself. Namely we need to ask, is the base at least one greater than the length of the representation of the number in that number system? This would rule out a lot of the results we could find using our script, but could be fixed by just adding a couple lines for this check.

Another important note is that, this is a procedural way to find what we’ve deduced as \(\gamma_{m}\). And while this has been really cool for me to discover, I’m wondering if there’s some formula that could generate this more efficiently. This problem is way over my head and would require someone more advanced than I in the realm of number theory, I’m envisioning some kind of Euler’s Totient Formula wizardry here with functions dealing with number systems.

Again, I’m sure there’s more to be explored with this kind of idea. I’ve really enjoyed poking around a bit and discovering this for myself, if you have other cool ideas you would like to work around do let me know!