The Chaos Game

Creating Fractals using Microsoft Paint

In Progress

This post will be somewhat different from the rest in that, I’m not really going to explain much here. The point of this post is to showcase something that I first came across a long time ago, and decided to recreate in MS Paint for fun.

The Motivation

I first learned about this so-called “Chaos Game” (which is actually its standard name) from this video back in high school. I thought it was super cool, but I haven’t really thought about it or seen it anywhere since then.

Fast-forward 5 years and I’m learning and playing around with pyautogui, a python library that lets me program mouse and keyboard inputs, just because I was curious to see how I could do that. I didn’t want to test my programs by just letting it click all over my screen, so I opened up Microsoft Paint - probably the most basic and primitive window I can use to click and track where I’m sending my mouse to go via turtle-esque function calls.

As I’m getting bored with just moveTo() and click(), I remember this one video I saw a long time ago that describes a game using just those two functionalities to create amazing fractal designs out of randomness - the Chaos Game.

I code up a pretty basic version of this game to be played within my MS Paint window and suddenly become engrossed with toying around with the rules and seeing what I get.

The Game

The Chaos Game is very simple. The most well-known result uses the following rules:

- Place 3 nonlinear vertices somewhere in the open space

- Place another point anywhere in the space

- Pick one of the 3 vertices at random

- Place another point that is halfway between the last point and the randomly chosen vertex

- Repeat steps 3 and 4 many times

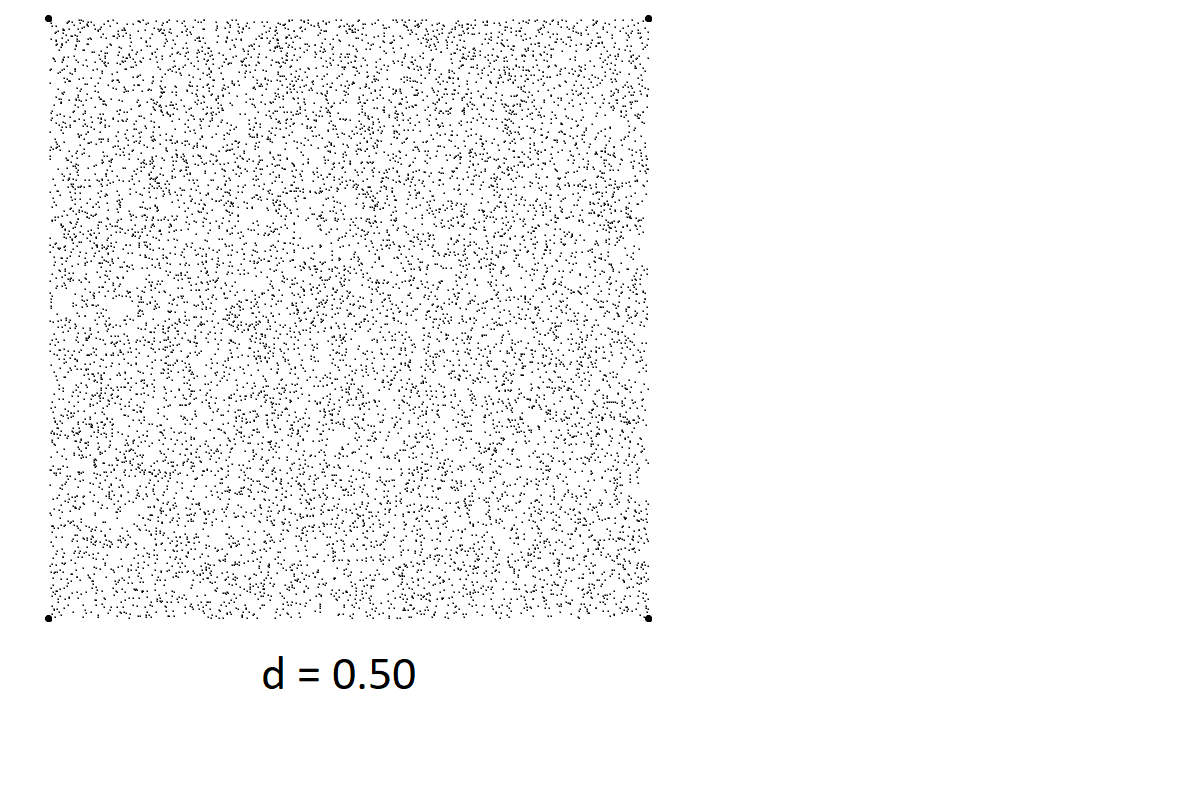

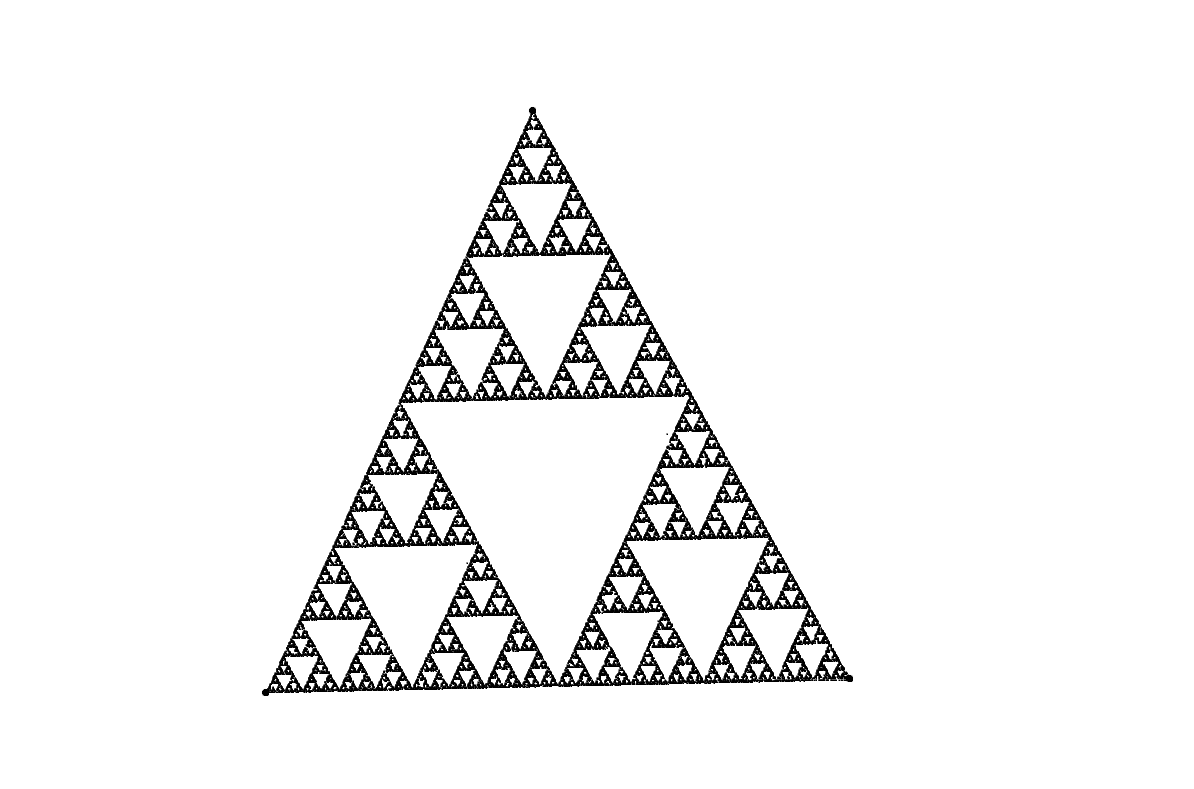

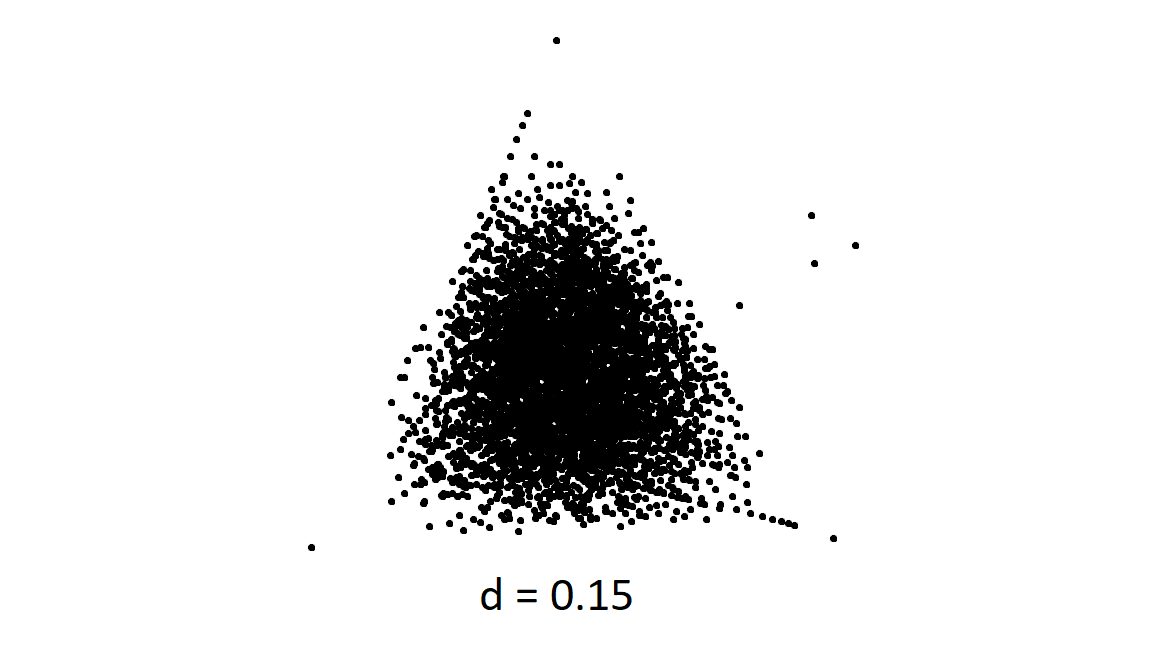

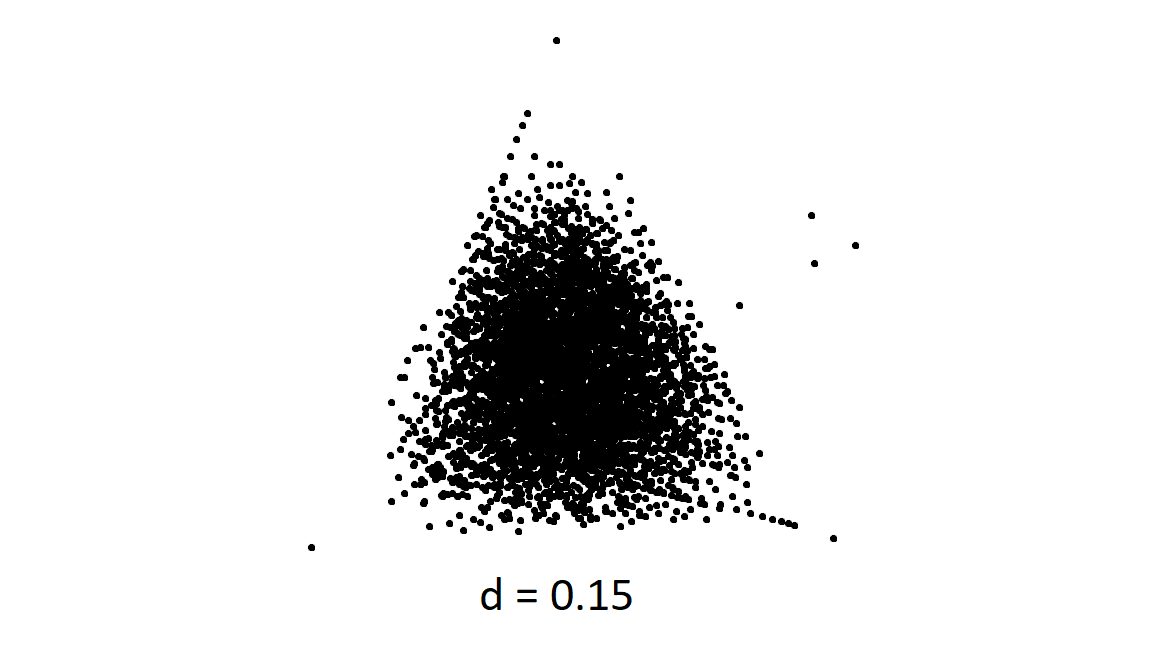

That’s it! Starting with 3 points on a triangle and randomly adding more points around the figure based on this “halfway” rule is the entirety of the game. Before I reveal what the resulting figure would look like under these rules, think on it for yourself - if we started with vertices like these below and a starting point anywhere in the plane, what would happen after doing this process, say, 50000 times?

Would the whole inside of the triangle be filled with scattered points? Would some kind of pattern emerge? Are there any points that are impossible to reach under these rules?

Well, here’s what actually happens:

Alright well we definitely know at this point that there’s something going on here. If you haven’t seen this before, the shape that we got from this very closely resembles the Sierpinski Triangle, a self-similar object that can be created by just drawing triangles within triangles ad infinitum.

This is super cool to me - that this super simple procedure with a very random nature is described by such a structured design. I won’t go into why this emerges, there are some good resources elsewhere online for this, but I instead want to showcase some results that can arise from muddling with the rules a little bit.

However, something that I noticed while creating and playing with my python script is that, if the starting point is a point that is not exactly on the Sierpinski Triangle (including adding larger triangles outside the starting vertices to account for the case where the starting point lies outside of the triangle defined by the vertices), then the pattern will never truly reach the Sierpinski Triangle exactly! It will just keep getting closer and closer to the shape as more iterations are run.

Along with this, I think that once a point is marked it’ll never be reached again. If this is true, then it follows that, if we know only the very last point chosen over the iterations, then we are able to trace backwards the exact series of points that were drawn to get all the way back to the start (given that our drawing is perfectly precise), which I think is pretty cool.

Side Note: I’m not a big fan of the name “Chaos Game” for this procedure. It makes sense intuitively, since the result of this game is order from seeming chaos (I mean, it is random for goodness sake, that’s about as chaotic and unpredictable as it gets). However, when we use the term chaotic in math to describe a system, we generally mean that the system is incredbily sensitive to initial conditions, where the tiniest shift in the starting inputs to a system drastically change the system’s behavior over time (see the double pendulum). But when we look at the chaos game, the results are just about the same regardless of the starting inputs (which is literally just the one starting point).

The Results

This is the fun part where you get to look at weird pictures of a ton of dots. All of the following pictures have been generated by my script (found in the next section) and drawn in Microsoft Paint. Click on any of the pictures to see an enlarged view.

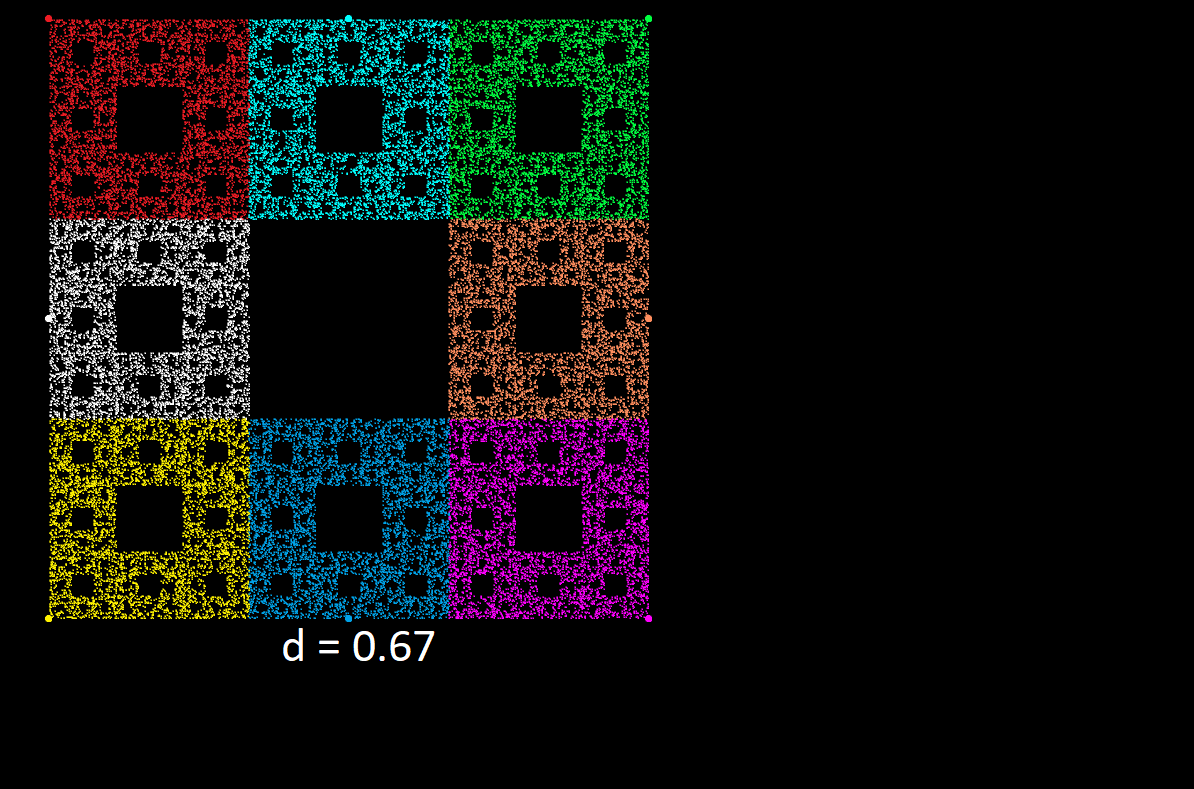

When I talk about “playing with the rules” of the chaos game, the first things that I tried were adding more vertices and changing how far to travel to the selcted vertex. In all of the following images, \(d = 0.40\) means that, instead of traveling halfway to the selected vertex at each step, you travel \(40\%\) of the way. Also, from here on out I’ll use the description of one vertex “jumping towards” another. What I mean by this is that, if we select vertex A and place our point wherever it should go, and then the next round we choose vertex B and place our point some distance towards vertex B, then vertex A jumped towards vertex B.

Some of these images have colored points, which are defined by the color of the vertex that the point is jumping towards. If a point is jumping towards a vertex labeled as red, then the point will be colored red.

One important thing to notice, is that not all rules for the game will produce a visually meaningful pattern. For example, here’s the same game as above just with an extra vertex:

TODO: Rerun like all of these with more dots and with color

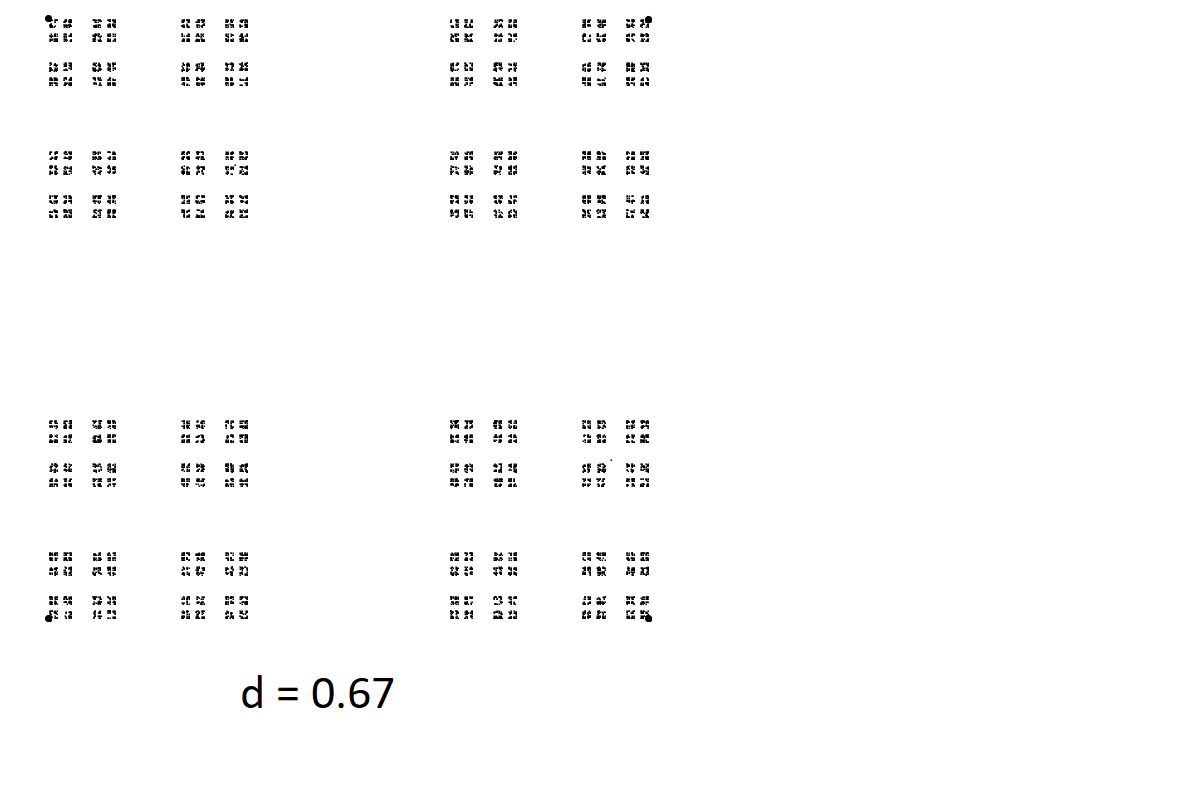

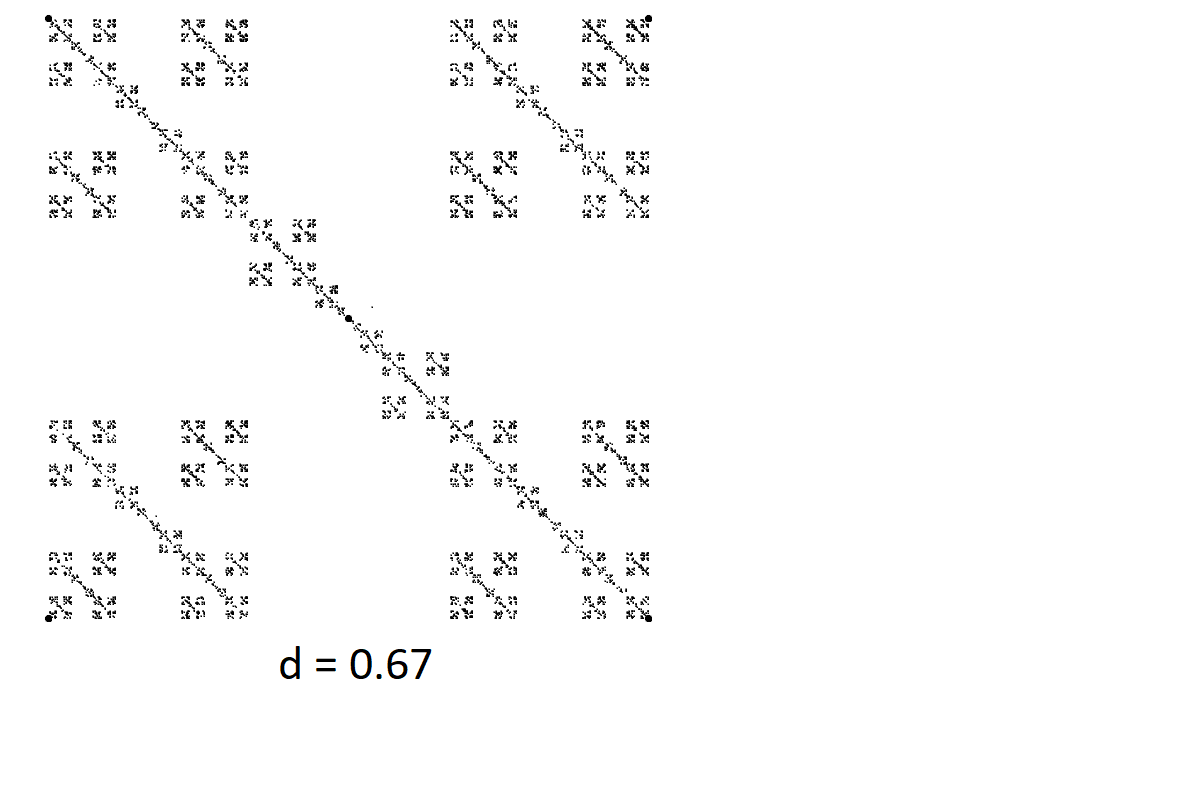

But notice what happens under a larger \(d\):

And, for fun, let’s add a vertex in the middle:

What if we couldn’t jump towards the middle one if we’re coming from the top right or bottom left corners? One thing I like about this one is that changing this rule for these two corners affects the entire picture. It makes sense why that diagonal line from the top right to the bottom left would be gone, but also notice how its gone from the top left and bottom right mini-squares too!

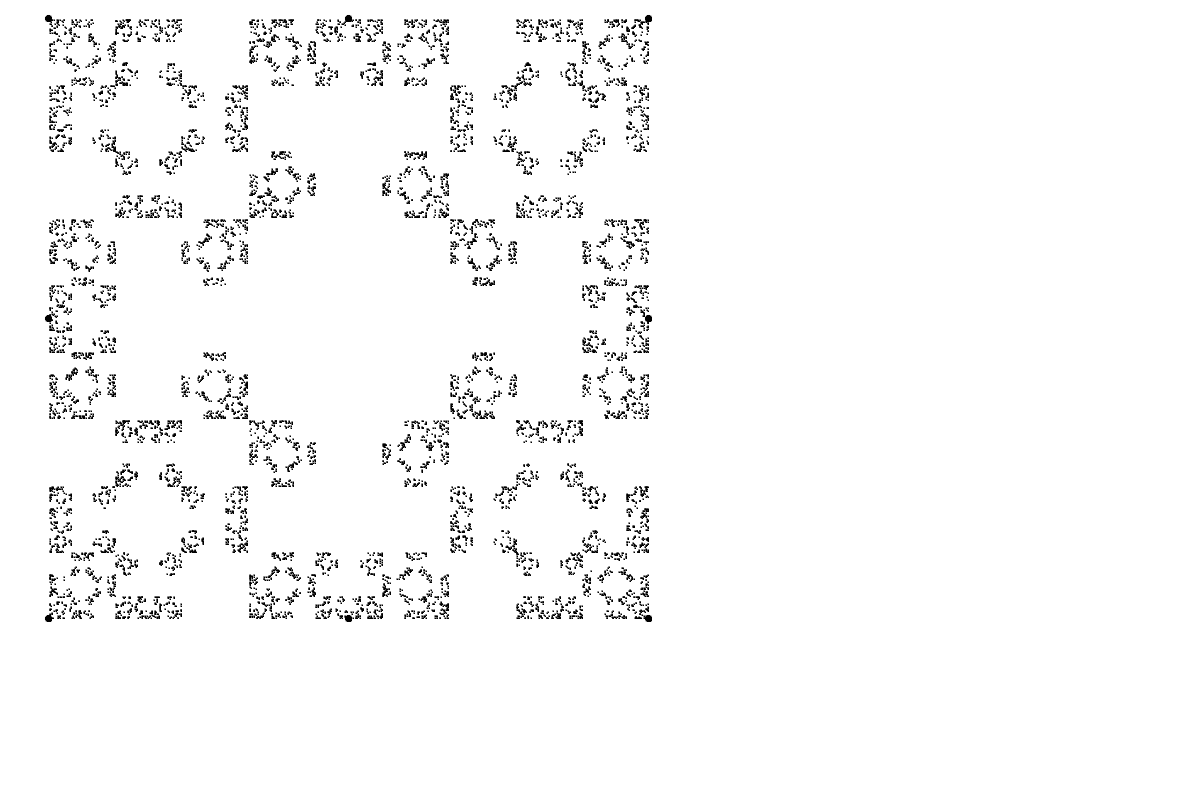

Another well-known fractal is the Sierpinski Carpet, and I wanted to see if I could find a rule configuration to generate this. It was a fun brain exercise to come up with what I have here:

Now lets say that any corner vertex can’t jump towards the vertex 3 spots away clockwise (can’t make a small CW diagonal jump), and the edge vertices can’t jump to the vertex immediately CCW to it. Weird rule, I know, but just check this one out:

What if corners could only jump to edges, and edges could only jump to corners? A vertex can still jump to itself here:

And if corners and edges can’t jump to themselves?

Ok now check this out. This is the same rule as just above:

What I find cool about this is that, in the earlier one, my eyes gravitate to see the “pattern” as the stuff defined in black, by the points themselves. However, just by changing the distance value, I now see the pattern as the white space, defined by the absence of points there.

The Code

I’ve put this section last on purpose - I want you to have the best understanding of the process as you can before using the script I wrote. Please read the comment at the beginning of the script before running it, and follow the directions that the popups prompt you to do. It also is worth running $ python chaos_drawing.py --help the first time to see all of the input arguments that are available.

Keep in mind that this script was made to be ran with Microsoft Paint. Other image editors will likely work, but may take some tweaking to the global parameters or to pyautogui’s variables.

If you haven’t done this before, you’ll need to

$ pip install pyautogui

I also recommend running python in unbuffered mode for stdout by using $ python -u chaos_drawing.py for certain output to look cleaner.

There is a getRandVertex() function in the script that is used at each step to get the random vertex. This is where you can mess around and change how vertices are selected, such as “don’t pick a vertex 2 vertices away from the previously chosen one.” I’ve left some of the additional rules I used for my drawings commented out if you want to try running with those and seeing how it turns out yourself.

One last thing to note for the script, is that VERTICES, the list of vertices, keeps track of all of the figure’s vertices in the order they were entered. This is important if you’re trying to implement a new rule such as the one above.

The Randomness

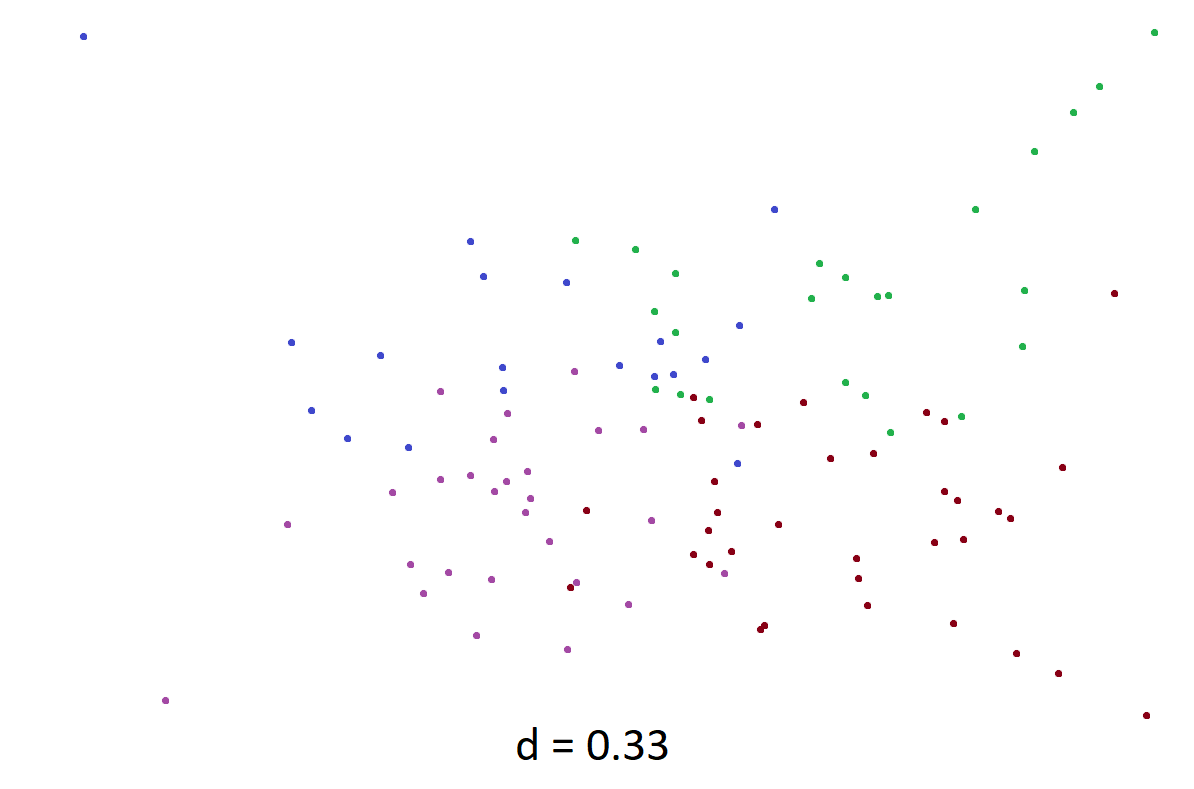

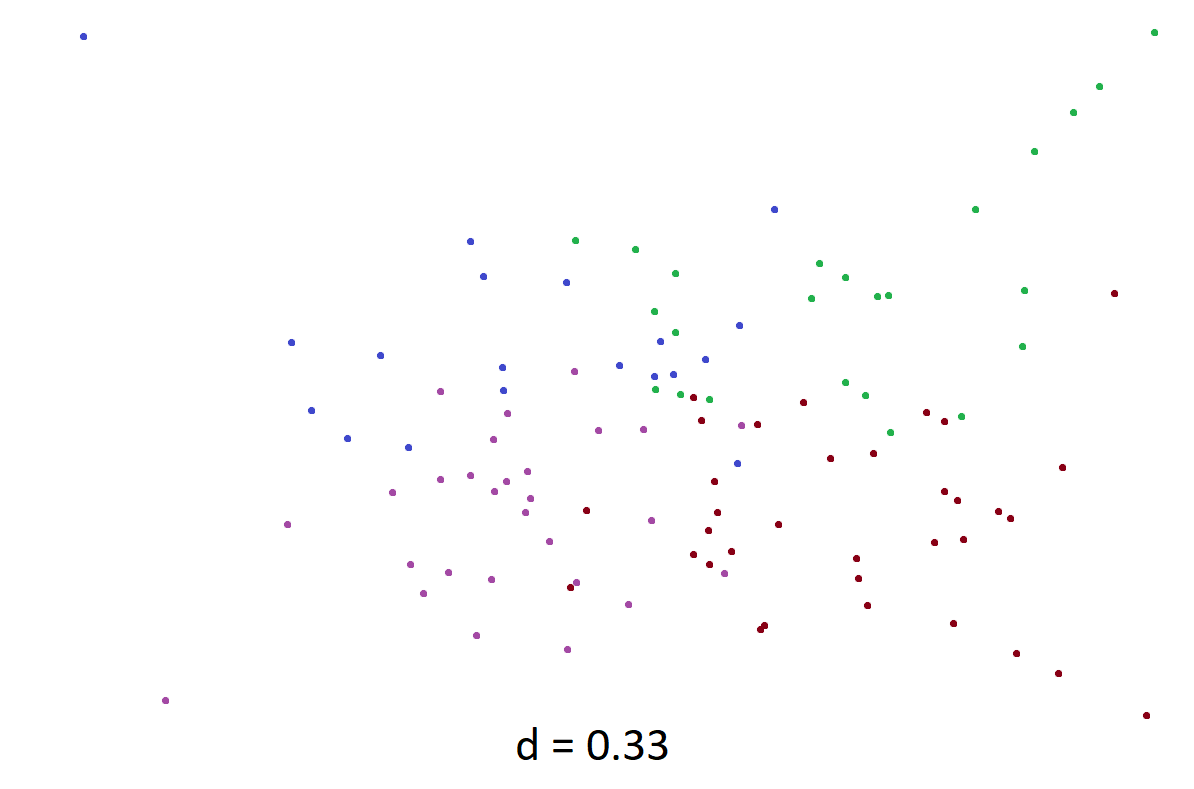

Something unexpected came up when I was making this that I’ve seen before in other contexts, and I thought this was a cool way to showcase it. Take a look at these pictures generated by the chaos game. What do you notice about these?

Before we answer this, lets take a quick detour through randomness.

Setting aside the realities of “random” and “pseudorandom” in computers for this discussion, what makes something “more random” than another thing? If I asked you which of these lists made up of numbers 1-4 is more random, could you give an answer?

\[[1, 3, 3, 1, 3, 3, 1, 3, 3, 4]\]

\[[2, 2, 3, 1, 4, 1, 3, 2, 4, 1]\]

Well I can say that one of these was generated by python’s random.randint() function, and one was me creating a sequence that looks random to me.

The random one is the first one. Yup! That pattern you see and those repeated numbers are purely coincidence and came out of the random number generator on my computer. If this is unsettling, remember that a list of all \(4\)s also has the same chance of arising as either of these specific lists by doing this - and that list wouldn’t seem random at all.

That’s the thing about randomness, is that true randomness will sometimes look deceptively orderly. This is because, even though our intuition might be quick to say that it should, one outcome of an event like this doesn’t effect the outcome the next time the event occurs. Our minds tend towards the Gambler’s Fallacy.

Randomness will sometimes look deceptively orderly, especially over longer periods of time. Let’s say we instead generated a list of 100000 numbers 1-4, it should be intuitive that there’s a pretty reasonable chance that somewhere in that list is a sequence of 10 numbers that are all the same, despite that going against our natural idea of what “randomness” should look like.

Let’s take another look at those pictures from before:

With the \(d\) values on each of these being so small, we would expect these graphs to look very cluttered in the centers, as with each step we aren’t moving too far away from the previous point. We see this happens for the most part, but we also see these “strings” of points all moving towards the same vertex. This can be thought of as (and this is in fact exactly what is happening) a sequence of the same value being chosen by a random number generator over and over.